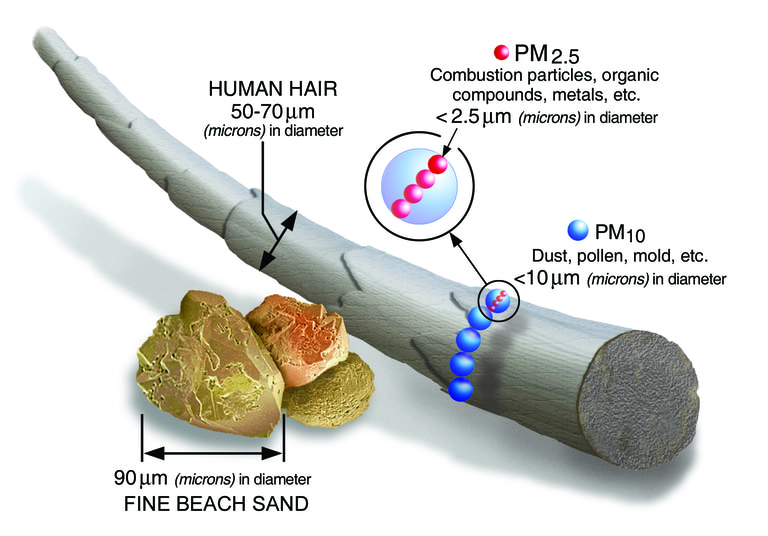

I lived for about three years in Beijing and Shanghai. This was around 2012, when air pollution was fast becoming a matter of concern. Multiple studies were singling out particulate matter below 10 µm in diameter (PM10) and below 2.5 µm in diameter (PM2.5) as key contributing factors to lung cancer.

Trying to protect both my then-girlfriend (now wife 💕) and myself, I started looking at air purifiers. But most purifiers, at the time, didn’t come with embedded air quality sensors. You were just supposed to turn them on and hope for the best. That’s unsatisfactory for several reasons:

-

How do you know if the air quality reported by third parties accurately reflects the air quality around your home?

-

In Shanghai, we were lucky to have the U.S. Consulate air quality monitoring station a few miles away, but it still didn’t tell us the air quality inside our home. Air purifiers get noisy at higher settings—how do you know if you can safely move to a lower setting or even turn it off for the night?

-

How do you know whether your windows and doors are leaking and letting in external pollution? Back-of-the-envelope math show that even small exchange flows with the outside can ruin your day. Buying adhesive foam or rubber liner at the hardware store can be a much better investment than buying additional purifiers.

-

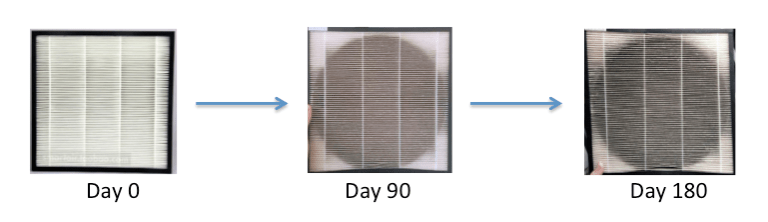

How do you know when to replace HEPA filters? My testing showed that if you eyeball it and replace filters when they look dirty, you are likely overspending. (Funnily enough, some filters capture a higher % of particles dirty than new. But as airflow decreases due to higher resistance, you still eventually end up capturing fewer particles per unit of time.)

I decided to buy an air quality sensor. At the time, the only widely available ones were the Dylos line of products. How these devices work is quite simple. A small fan creates an airflow through a duct; a laser shines a beam through the airflow; and a photodetector registers when the beam is scattered by particles in the airflow. If you want to know more, there’s a good teardown.

This gives us an estimate of the particle count per unit of volume. In our case, Dylos displays the particle count per 0.01 cubic foot of air. Yes, that’s barbaric, but it’s America and everything is possible, so I’m just grateful they didn’t do it in fl. oz.

More expensive air quality sensors, like the ones used by governments, do not use the laser approach, and measure PM2.5 in a more civilized µg/m3.

The issue is that there is no exact conversion from particle count to weight. Fortunately, correlation is high and approximate conversion formulas exist. This allows us to compare interior air quality measured by a Dylos, with exterior air quality measured by a government station.

The Dylos was instrumental (/r/dadjokes) in helping me fight pollution in my home in China. At the end of the day, though, it was a losing fight. Staying stuck in your home because going out may give you cancer is exactly as awful as it sounds. There’s probably a dystopian YA movie somewhere with a similar plot. (It also reminds me of Hugh Howey’s excellent Wool series.)

China sacrificed the environment to let breakneck industrialization raise hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. I don’t completely blame them, but I do feel hugely for the people and families who live there. And now that I’m back under the blue skies of Northern California, I know exactly why they are worth preserving.

Part 2 will be about how to pipe together a Serial-to-USB cable, a Raspberry Pi, Redis, InfluxDB, Grafana, and Rust to stream Dylos measurements straight to my homepage.